Try thinking back on some conversations you’ve had with a biased person.

They tend to interpret things in ways that don’t seem objective or are clearly self-serving.

These tendencies might seem harmless in casual conversations, but in negotiations, cognitive biases can lead to suboptimal outcomes if we don’t catch ourselves in the act.

We’ve covered a fair number of common cognitive biases that could plague any negotiator, and this post is to give you a quick overview of them all.

What Are Cognitive Biases in Negotiations?

When your current understanding of the matter is different from what the matter is, you have a cognitive bias.

Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking that arise from our brain’s reliance on mental shortcuts. These are mental shortcuts that we take to draw conclusions faster but lead to judgments and decisions that deviate from rationality.

In everyday situations, cognitive biases might be harmless or even helpful. But in negotiation, slower, more deliberate thinking is crucial.

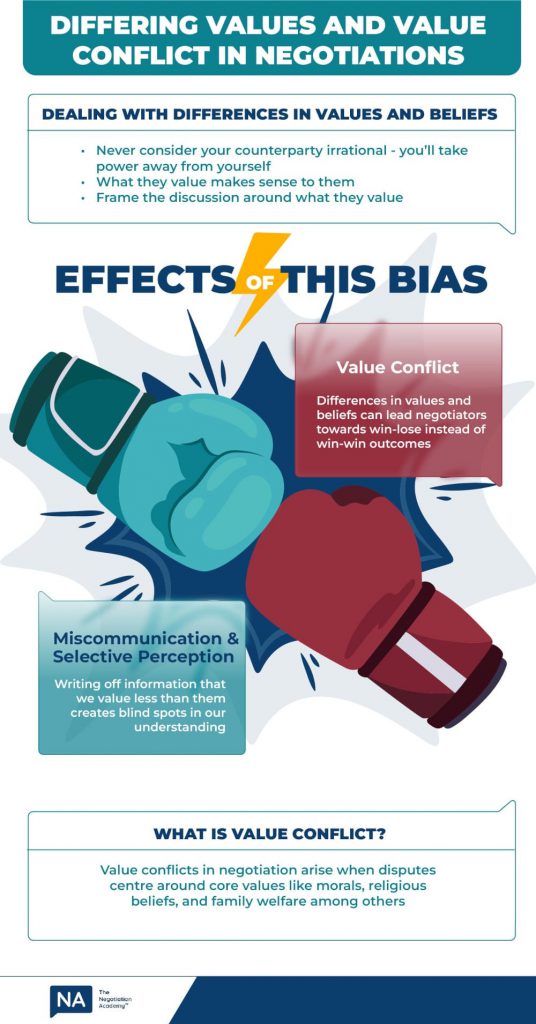

To better understand cognitive biases, it helps to review Kahneman and Tversky’s System 1 and System 2 thinking from their book “Thinking Fast and Slow”:

System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive. It operates with little effort but is also prone to biases and errors. It is responsible for quick judgments and impressions. We make most of our daily decisions using System 1 thinking (think about 95%).

System 2 is slow, deliberate, and analytical. It requires more cognitive effort and is used for complex reasoning and problem-solving. It monitors and evaluates the decisions made by System 1 but is often lazy and easily distracted, leading to reliance on System 1’s quick but sometimes flawed conclusions.

In negotiations, relying too much on System 1—trusting our gut feelings—can lead to biased conclusions. Taking time to slow down and analyze the situation using System 2 can help counter these biases.

We cover more detailed examples of how System 1 and System 2 thinking affect negotiations in this blog post.

Types of Cognitive Biases in Negotiations

There are many reasons why cognitive biases in negotiations happen, such as latching on to initial information too tightly or even your inherent values and beliefs.

Here’s a quick list with links to their more detailed articles:

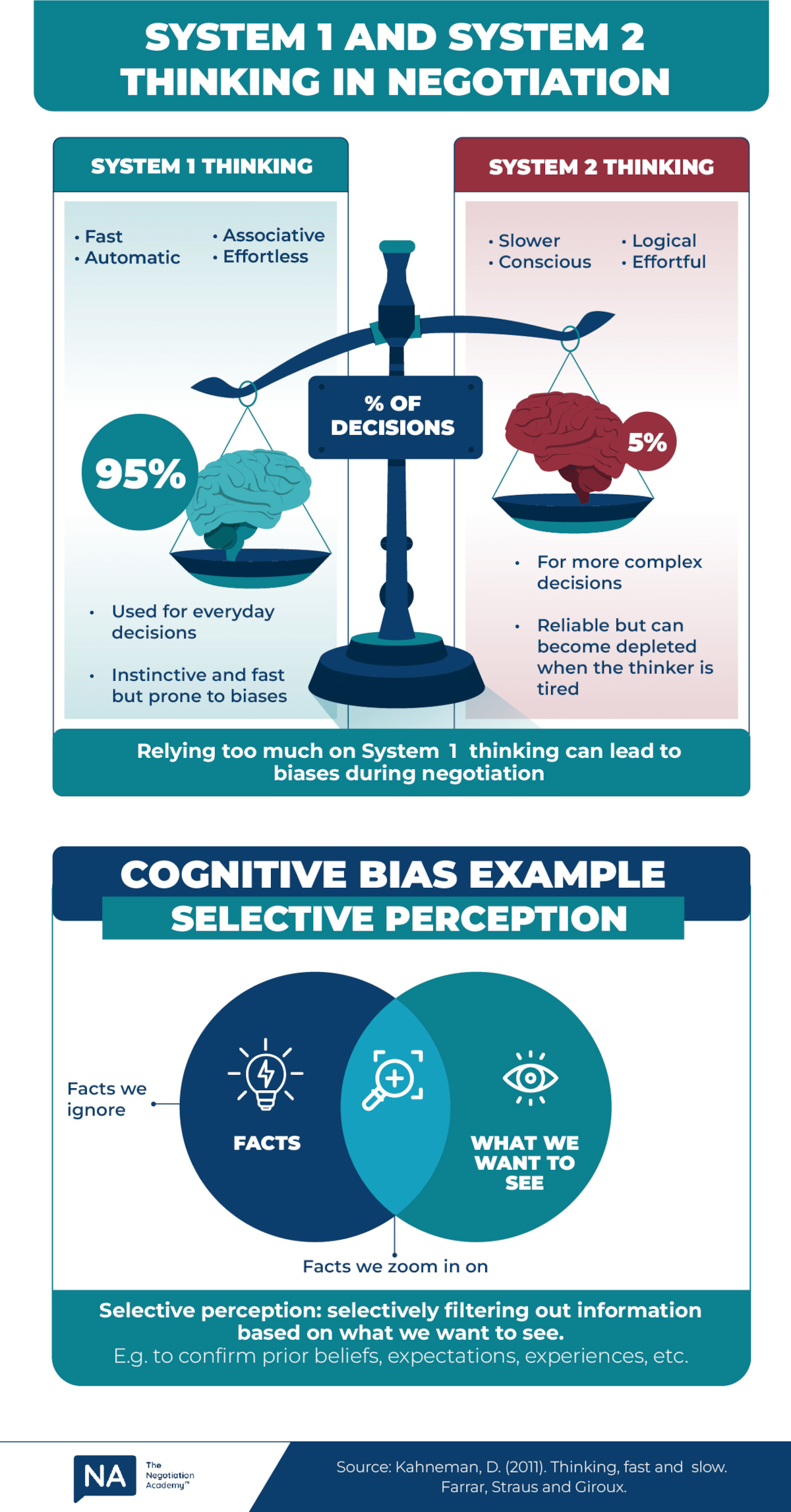

Selective Perception

Selective perception refers to people’s tendency to interpret information to confirm their beliefs, impressions, and experiences. This can go as far as selectively filtering out information that doesn’t help us get what we want.

Example: Imagine presenting the same evidence to both the plaintiff’s and the defendant’s lawyers in a case. Each lawyer may interpret the evidence differently based on what benefits their client.

Read more on selective perception here.

Framing

How an offer is framed will affect the way we interpret and react to it. Here are two examples of how this could happen:

Loss Aversion – The pain we feel from losses tends to be felt more than the joy from gains, so people try to avoid losses whenever they can.

Certainty Effect – The certainty effect happens when people prefer guaranteed outcomes compared to probable outcomes. This leads to people avoiding risk when there is one of their options has guaranteed results.

The reverse is also true, where they want to avoid guaranteed losses and pick probable gains. This preference persists even if the probabilistic option could have a better payoff

Both of these biases are key components of Kahneman and Tversky’s Prospect Theory. You can read more about how framing works in negotiations here.

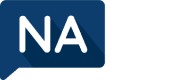

Differences in Values and Beliefs

Differences in values and beliefs can manifest problems in different ways. If you enter a negotiation with somebody you have enmity with, that could lead to win-loss mindsets.

Value conflict could also lead us to selectively ignore or leave out key information they provide if we choose to value the information less than they do.

Offers that don’t align with the values and expectations of the other side could also be rejected out of principle, even if it is an objectively good deal.

Example: In labor negotiations, a company may value profitability, while a union prioritizes worker well-being. This value conflict can lead to deadlock, even if both parties stand to gain from an agreement.

To get more details on this cognitive bias, read more here.

Perceptions of Fairness

People reject outcomes they perceive as unfair, even if it results in worse outcomes for both parties.

Example: In this Ultimatum game social experiment, two parties were given money to split among themselves. The condition is that they could only receive the money if both parties agreed on the amount. The splits were closer to equal splits of the money as the receiving party would choose to reject offers and walk away with nothing rather than accept an outcome they perceived as unfair.

In negotiations, parties tend to select standards of fairness that benefit their side the most. To find out 4 of these standards, check out more in our fairness article.

Overconfidence

This comes across as more of an attitude instead of a cognitive bias, but it is actually a cognitive bias all the same.

Overconfidence bias happens when we overestimate our abilities, judgments, and estimated success while underestimating all these aspects of our environment or counterparty. This hampers our assumptions, judgements and estimations of success – which can all hamper our decision making during negotiations.

Example: A negotiator may assume they know exactly what the other party wants, only to discover that their assumptions were completely off, leading to a missed opportunity for a deal.

Find out more about overconfidence here.

There are plenty of other cognitive biases that we haven’t covered yet, but just familiarising yourself with some of these can help you to keep your own biases in check.

Ever wanted to see some of these in action? We have live demonstrations of these biases in action during our live negotiation workshops.

Curious? Contact us and sign up for one of our workshops or online courses today!

To your negotiation success!

We share a lot of what we’ve learned by training businesses and law firms with their negotiation in our online courses and live sessions.

Joining one of our courses will put you on par with over 10,000 leading lawyers from Fortune 500 companies to Tier 1 law firms globally, boosting your negotiation skills to new heights.

If you want to see how these biases happen in real life, try one of our online courses or join a tailor-made live training session for your organization!